The Equitable Access Lottery Preference: Tweaking on the Margins

The DC Policy Center recently released a report on the MySchool DC “equitable access” lottery preference. The report provides decent analysis, but it left me with more questions than answers. What I really wanted to know was, to what extent did the equitable access preference change the status quo?

Equitable access gives a special lottery preference (like sibling) or sets aside a certain number of seats for students classified as “at-risk”. “At-risk” in DC is defined as receiving food benefits, experiencing homelessness, or in the foster youth system, and “at-risk” students comprise about 50% of students in DC. We know that “at-risk” students are underrepresented in the MySchool DC lottery in general and underrepresented in the most sought-after schools in the city. The “equitable access” lottery preference is intended to increase access to sought-after schools for “at-risk” students. But does it do that?

First, how many schools opted to offer an equitable access preference?

And the answer was, not many, particularly not many serving very few “at-risk” students. Across both sectors, the list of schools participating in the equitable access preference wasn’t consistent with what one would expect to see for a progressive city that prides itself on “leveling the playing field” with school choice. What’s worse is that some schools serving the lowest percentages of “at-risk” students in the city champion equity, diversity, and inclusion on their school websites. But actions speak louder than words, and if schools really cared about equity, then they would have opted to implement the equitable preference. It’s my position that if schools are unwilling to serve a representative sample of DC public school students, they should not receive public funding to run public schools, period.

DCPS schools are somewhat different than charter schools because most DCPS schools have to serve all students within their boundaries and often do not offer many out-of-boundary seats. However, there are “citywide” DCPS schools without boundaries. In addition, nearly all DCPS schools offer *some* out-of-boundary seats—but not necessarily for entry grades—and none of the DCPS schools serving <20% of “at-risk” students offered equitable access.

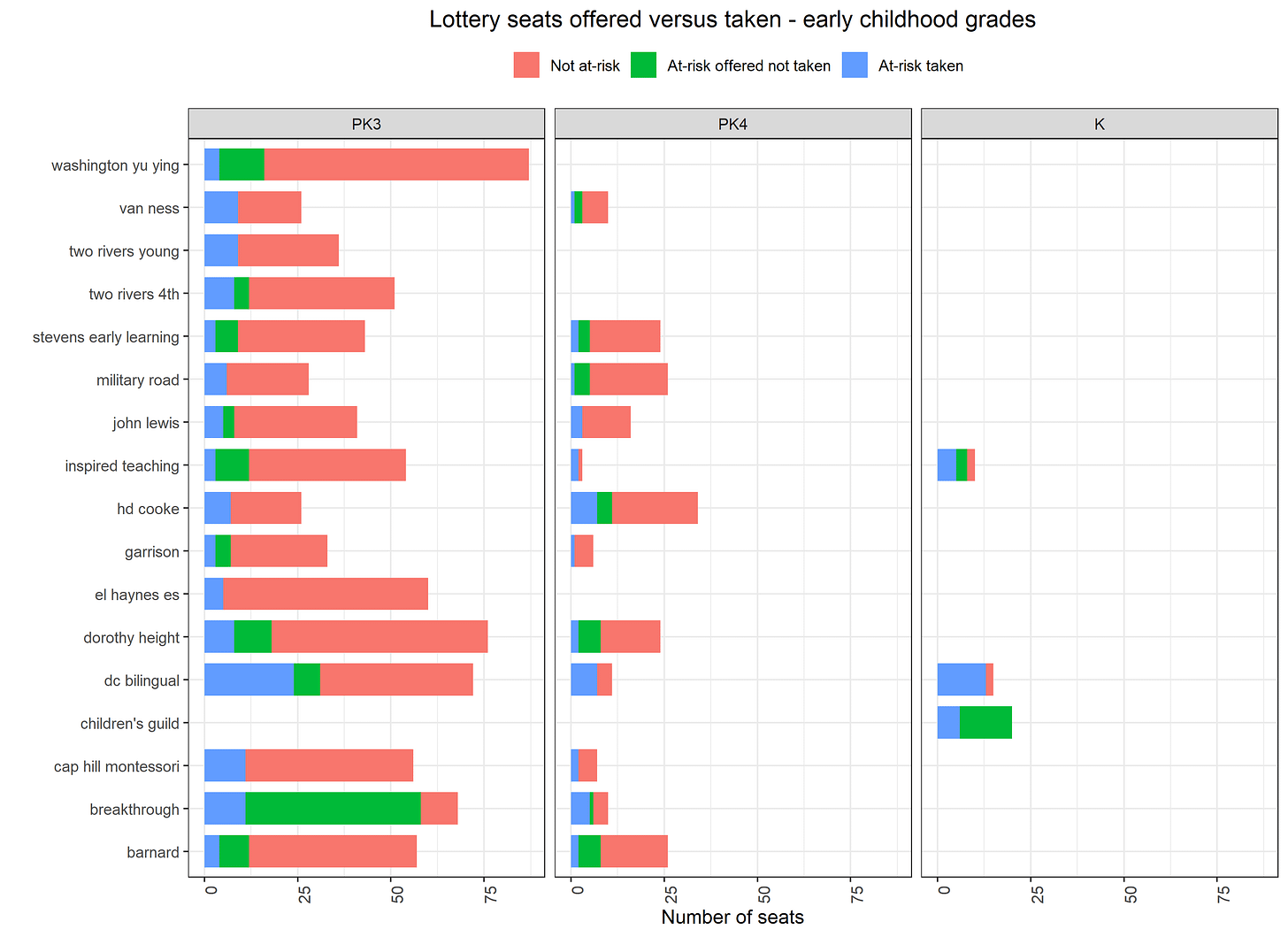

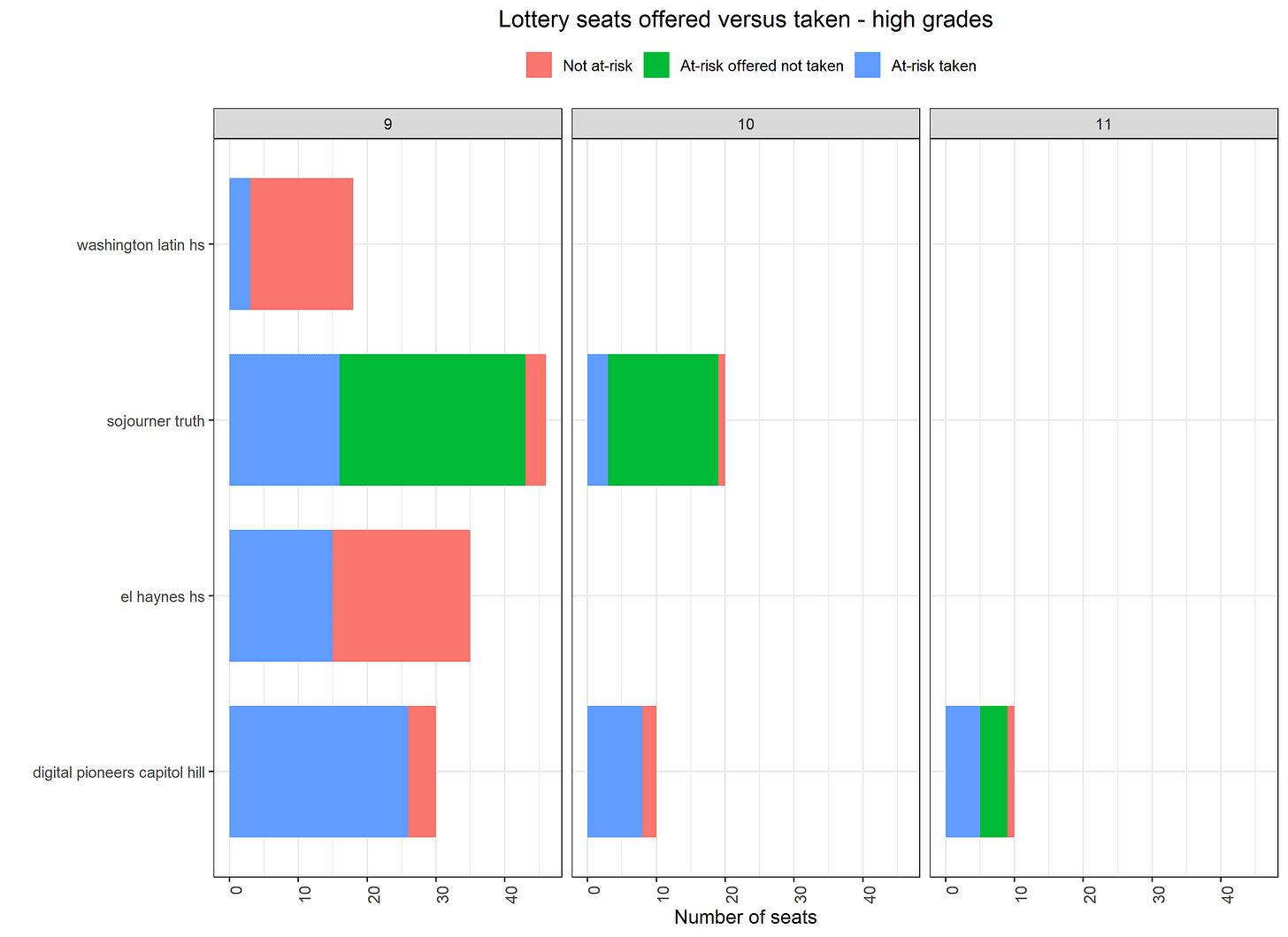

Second, how many seats did participating schools make available for the equitable access preference?

Participating schools offered relatively few seats for the equitable access preference— 50% would be representative. From the following graphs, we see that there wasn’t an attempt to substantially change the percentage of “at-risk” students for most schools. Moreover, not all equitable access seats offered were filled. Unfilled seats could be from lack of targeted outreach, inconvenient geographic locations of schools, or lack of desired programming at the schools.

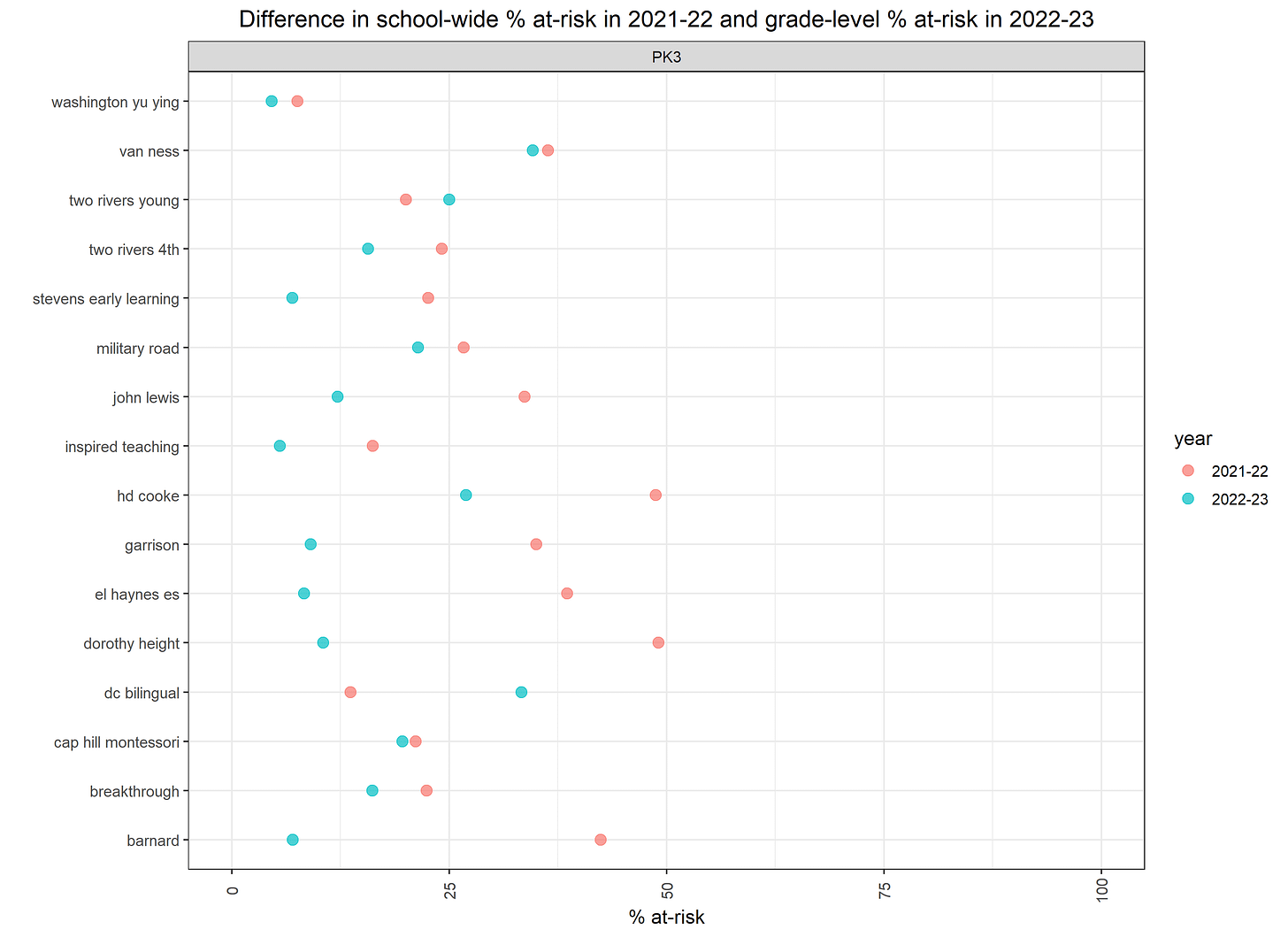

Finally, did the equitable access lottery preference meaningfully change the percentage of “at-risk” students in the participating schools and grades?

Because if equitable access did not make a meaningful difference for schools serving very few “at-risk” students, then what is the point? To figure this out, I pulled school-wide demographics from 2022 because OSSE doesn’t make demographic data by grade publicly available, and I don’t have an extra 6 months to FOIA the data. Therefore, I had to assume all grades within a school had similar demographic compositions in 2021-22. Then, I simulated how the grade demographics would change in 2022-23 as a result of equitable assess by pulling in lottery data from the entry grades. This assumes that all students who were matched in the lottery actually attended the schools. Therefore, the percentages of “at-risk” students in the following graphs are not exact.

We can see that equitable access did not result in higher percentages of “at-risk” students in the entry grades compared with the school-wide percentages of “at-risk” students in most cases. This is largely due to schools not offering many equitable access seats in the first place, and entry grades likely serving fewer “at-risk” students relative to school-wide percentages. The cases where equitable access seemed to make a positive difference was when the school offered relatively more equitable access seats (DC Bilingual) and when schools served very few “at-risk” students to begin with (Washington Latin).

Responses to the equitable access preference have been telling, to say the least.

The Deputy Mayor of Education’s Boundary Committee recently discussed expanding the equitable access preference. One of the stated concerns against the proposal stopped me in my tracks. The concern was that schools with few “at-risk” students would not have the “Title 1 budgets to support the new ‘at-risk’ students”, which is basically making the argument that “at-risk” students would not be well served in schools serving affluent children.

We actually have evidence to the contrary, that “at-risk” students have higher achievement in schools serving affluent children. Granted, we don’t know why that is the case, but still. We also know from a previous DC Auditor report that some resources are better in schools serving affluent children, such as the ratios of mental health professionals to students with IEPs. Finally, the amount of Title 1 funding is not nearly enough to fund any serious programmatic investments. For example, Title 1 money might get you one additional full-time teacher for the entire school. But none of this really matters, because the stated concern was really about people not wanting to dedicate seats at their choice schools for “at-risk” students without actually having to say that out loud. Others were not so coded in their racism.

I was glad to see the Boundary Committee ultimately recommended expansion of the equitable access preference at schools serving less than the citywide average of “at-risk” students. But the Boundary Committee also left it up to each LEA to decide how many seats to commit to equitable access, which is a major barrier to expansion.

Even the former Executive Director of the DC Charter School Board, Scott Pearson opposed requiring an equitable access preference, to the point he resigned from the cross-sector Advisory Committee on Student Assignment over it. If charter schools really existed to “break the link between student zip code and school quality”, then education leaders would be all over the equitable access preference. But choice is DC has never prioritized equity, and instead has prioritized school autonomy and individual preferences, which has in turn, decreased equity.

So should we expand the equitable access preference? Yes. Will it make a meaningful difference without more structural changes? No. Can we assume that schools and LEAs are going to expand equitable access preference without being forced to? No. And so DC continues to tweak on the margins, while patting itself on the back for doing so. Rinse and repeat.